Flavor of Truth

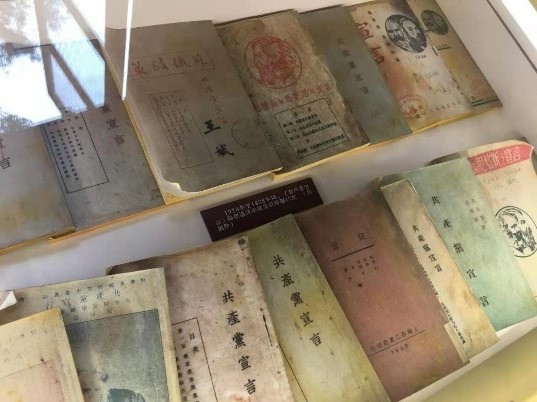

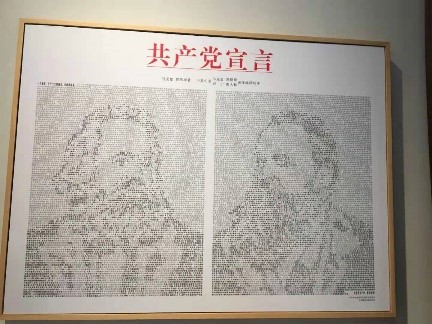

In the early spring of 1920, it was still quite cold in the mountainous area. Chen Wangdao hid himself in a quiet firewood house near his old house in Fenshuitang Village. He used two long benches, and a plank to make a desk, and laid a few bundles of straw over the mud as a stool. After nightfall, he lit up an oil lamp and immersed himself in translation under the dim light. The working conditions at that time were verypoor and the firewood house wasin disrepair for years.. In particular, when the evening came, , the biting cold wind often hit him through the leaking walls, making his hands and feetbecome numb and cold. Nevertheless, except three meals sent by his mother, he devoted all his time and energy to translating The Communist Manifesto in this humble house.

Professor Deng Mingyi ,in his book The Story of Chen Wangdao , described in detail the story of Chen Wangdao dipping rice dumplings in ink and eating them unconsciously. Seeing him getting thinner and weaker because of overwork, his mother felt worried and brought him some rice dumplings. Yiwu is known for its brown sugar. When his mother brought the rice dumplings to him, she also brought him a dish of brown sugar. After a while, his mother asked him if he needed more brown sugar and he replied again and again: Sweet enough. However, when his mother came in to clean up the dishes,she burst into laughter as she found he had a mouthful of ink. It turned out that Chen Wangdao was so absorbed in translation that he even didn’t notice that he dipped the rice dumpling in ink. It is on such occasion that the first Chinese version of the Communist Manifesto was born.

Chen Wangdao adopted a rigorous and meticulous attitude rgtowards his translation work. In order to make the translation faithful to the original work, ni, he looked up in the Japanese-Chinese Dictionary and English-Chinese Dictionary, andchoose words and sentences carefully. . The original version of The Communist Manifesto was in German. At that time, Chen Wangdao had at hand The Communist Manifesto translated by Kotoku Akumi and Toshihiko Sakai, which was published in the 1906 inaugural issue of the Japanese Journal Socialist Studies. This Japanese version was translated from the English translation by Samuel Moore, not from the German original.

1920年的早春,山区的气候还相当寒冷。陈望道躲进分水塘老屋附近的一间僻静的柴屋。端来两条长板凳,上面横放着一块铺板当做书桌,在泥地上铺上几捆稻草当做凳子。入夜后,点上一盏油灯,借着昏暗的灯光,埋头翻译。当时的工作条件十分艰苦,柴屋因经年失修破陋不堪。尤其到了晚上,春寒料峭,刺骨的寒风透过四壁漏墙向他袭来,常常使他冻得手足发麻。但他只是凭借柴屋里简单的用具,以及老母亲给他送来的每日三餐菜饭,夜以继日,孜孜不倦,翻译出了我国第一本(全译本)《共产党宣言》。

陈望道对翻译工作相当严谨仔细,为使译文准确符合原意,他不时翻阅着《日汉词典》、《英汉词典》,时时刻刻聚精会神斟词酌句,一丝不苟。《共产党宣言》原版是德文,而当时陈望道手中持有日本《社会主义研究》杂志1906创刊号刊载的幸德秋水、堺利彦合译的《共产党宣言》。这个日文本是转译自塞缪尔·穆尔(SamuelMoore)的英译本而非德文原本。